Omens and Observations

- Harry Clewans and Arthur Gonzalez at the Gearbox Gallery

- September 11 through October 10, 2020

- Fridays and Saturdays, noon to 5:00 p.m.

Harry Clewans is an artist and member of the Gearbox Gallery and works in his studio not far distant from the gallery. I met with him there to conduct a “studio visit” and do this write-up in advance of his upcoming gallery exhibit. As is my practice, I took my cell phone and used an app to record our conversation of about an hour. Unfortunately, the phone malfunctioned after eighteen minutes and I lost the rest of our discussion. So, the first part of this will follow our dialogue but the remainder will be from my recollection of the conversation. Hopefully the two parts will give you an idea of who Harry is and what his art is about.

So, here we are. Where to start? What interests me most is where you’re coming from. You’re talking about people?

Well, actually, most of them were not portraits. Those are more recent. But, yes, it’s usually figures.

Figures in bizarre landscapes. It’s always a little eerie. So what’s that all about? Maybe talk about the process.

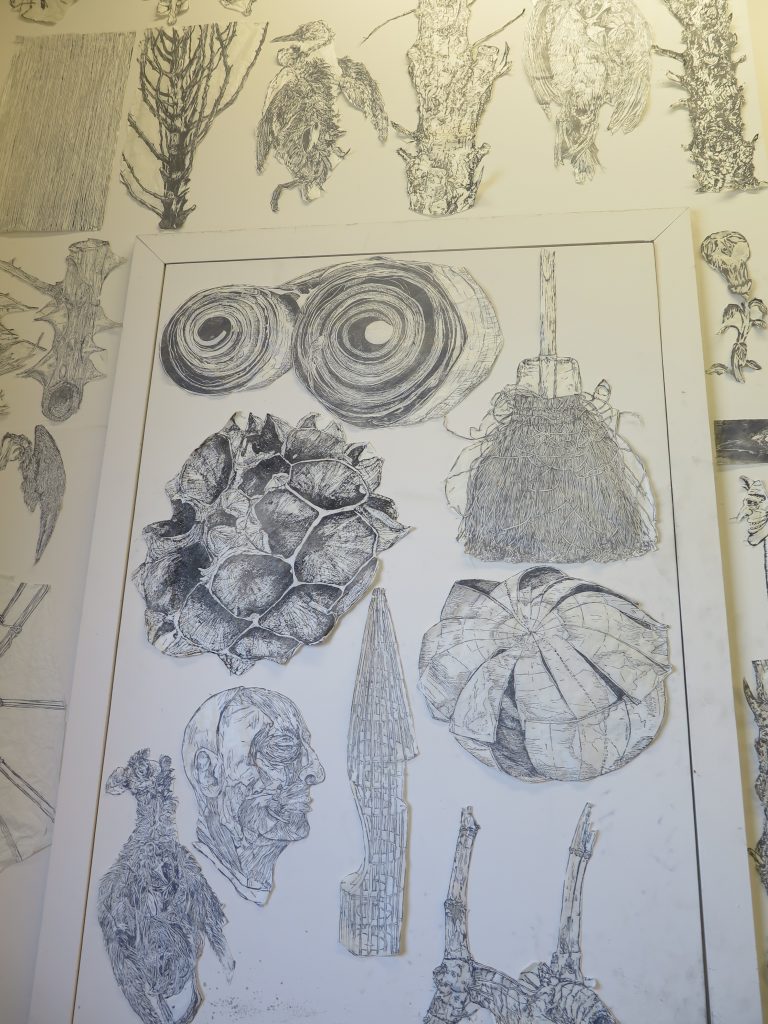

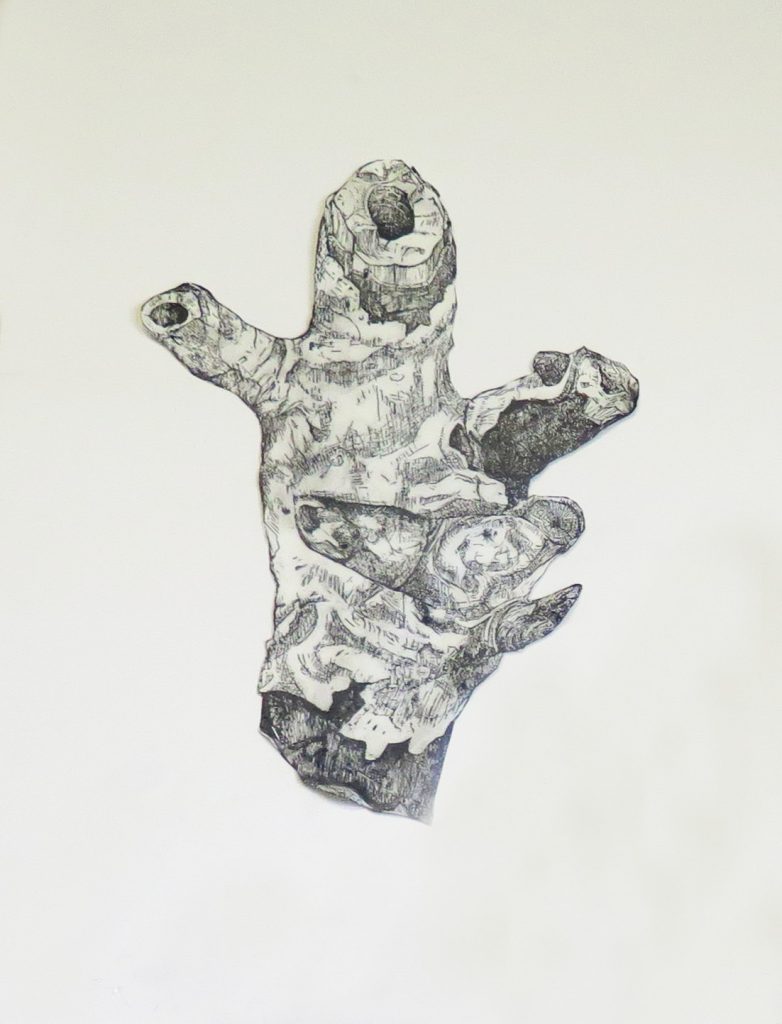

Those are all woodblock prints from blocks that I carve of objects that I find, like that piece of birch bark. I save a lot of things.

Sometimes they are rather small objects.

They’re usually very small. I’ll just stare at it in a non-judgmental way, without trying to figure out what it is. And then I’ll make a very detailed drawing, directly onto the woodblock. So this is one of those lighter fluid bottles. You remember, for barbecues? I found it on the beach.

And so I will look at it to do the carving, on pear wood, for the woodblock print. And I’ve been doing these prints for a long time, maybe thirty years or more. And then I started combining them together.

It must take a long time to do the carving; they’re so detailed.

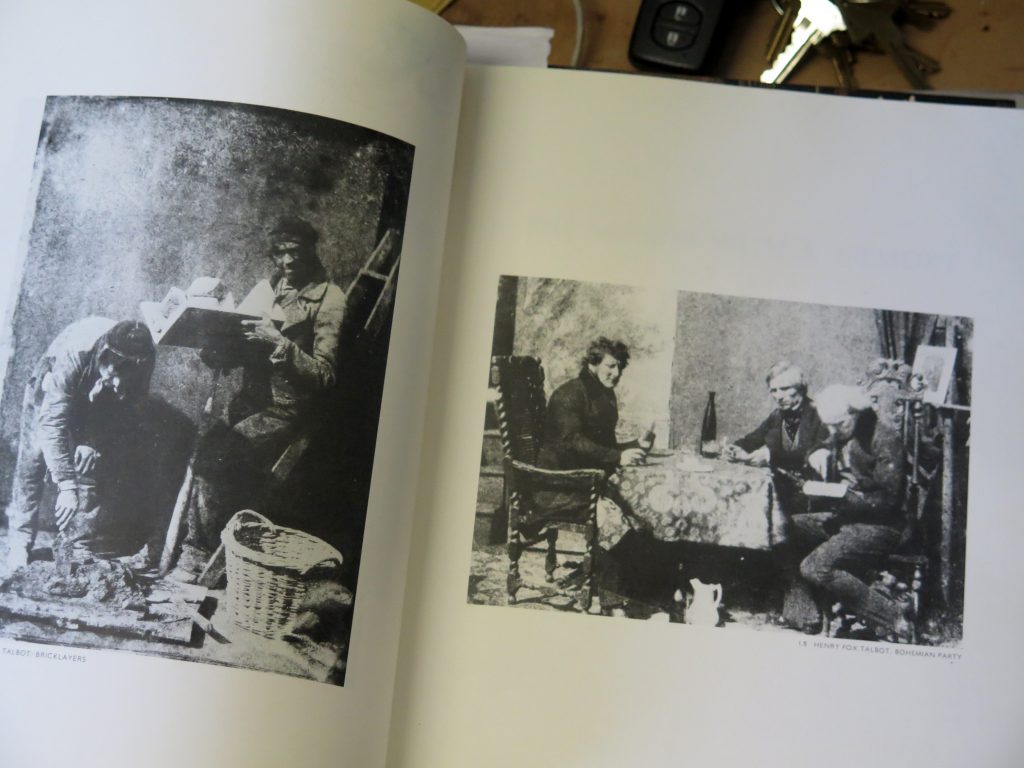

Sometimes two weeks or more. There was a tradition of wood engraving in the 1800s that interests me [Harry opens a book to show me an example.]. Look at the detail. I don’t use a press, just print by hand and sometimes not the entire block but just a part of it and I don’t do editions. For me, the prints are a step in the process, not the final outcome of it.

So you have a whole wall of these prints. Then what?

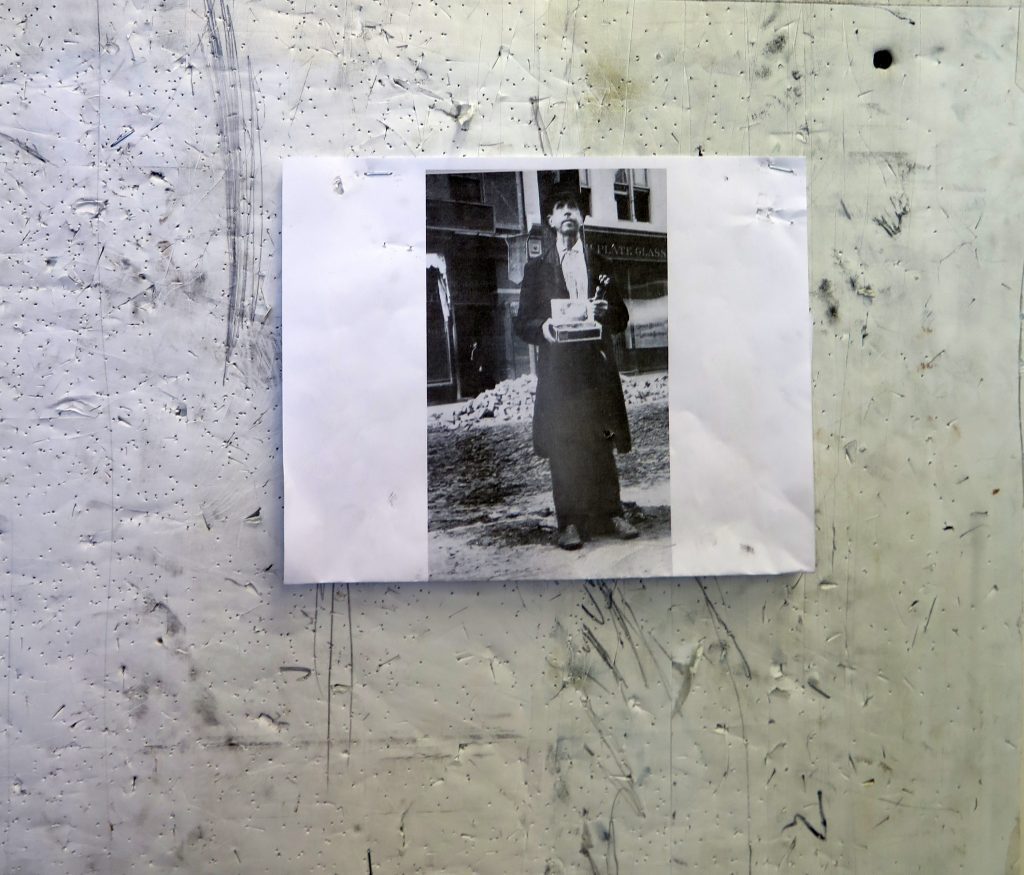

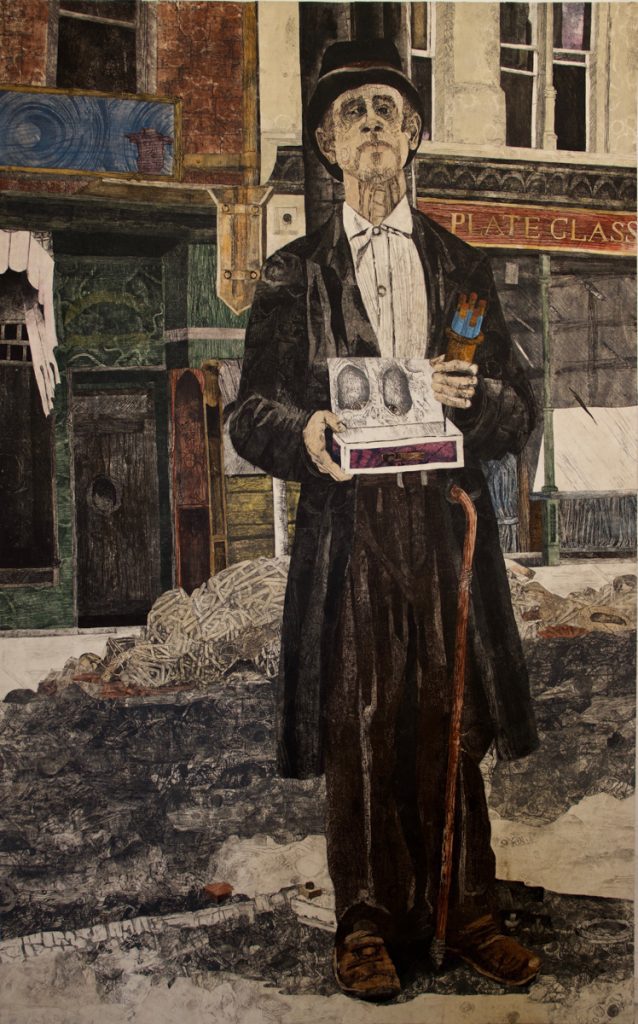

Then I find a subject, a photograph. And it could be anything; landscapes, figures, whatever. I like old photographs.

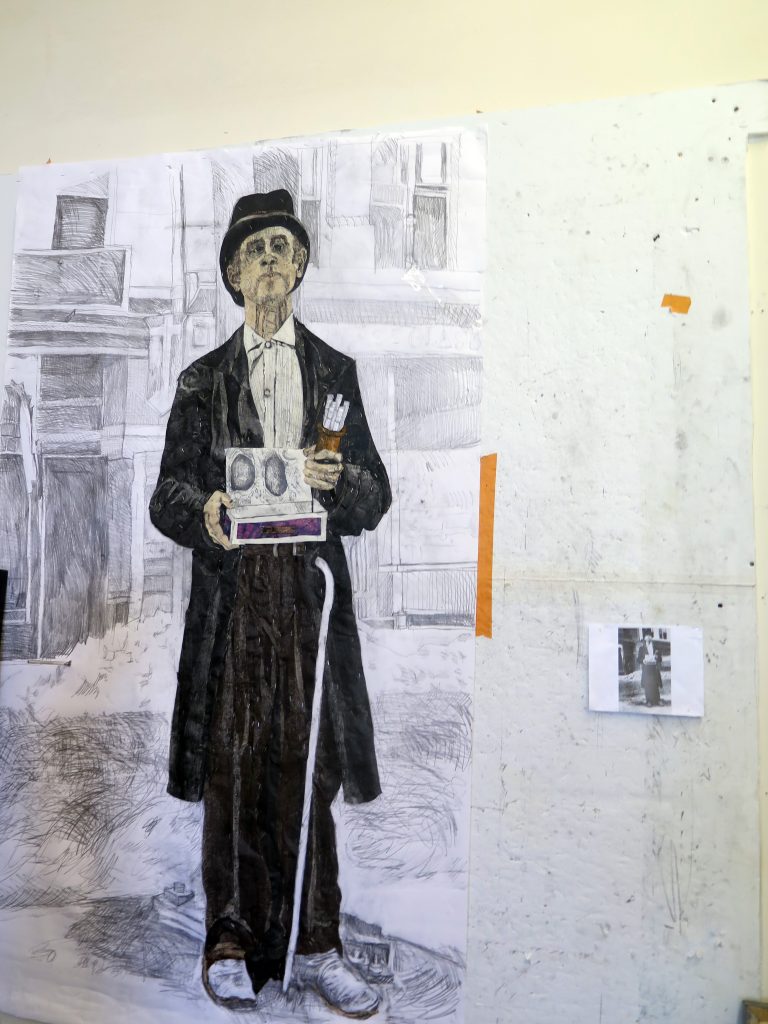

And I make a drawing of it and then use an overhead projector to project a line drawing on the paper [full-scale paper mock-up] and then go back in because it just gives you an outline. And then I begin cutting up and stapling in pieces of the prints into the mock-up.

Into the figure?

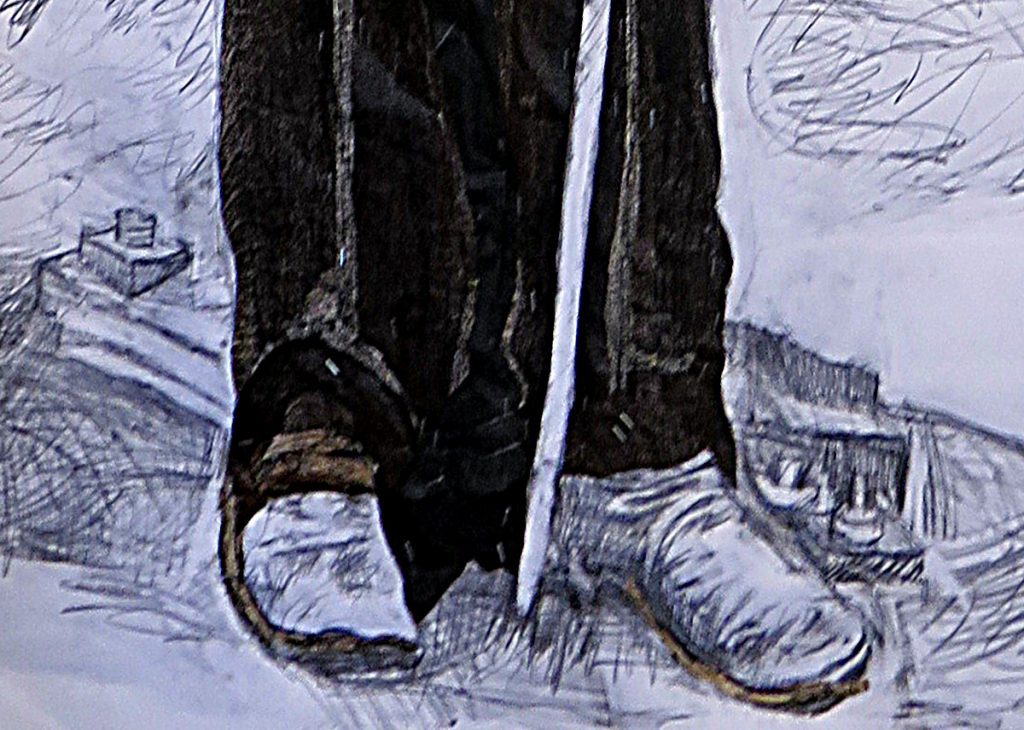

Yes, I always begin with the figure and then go to the background. So that root you see there, I have cut up and begun to fill in the shoes on the figure.

So you fill in all of the figure and then the background, whatever it is, a landscape or an interior, with all the cut up little pieces of the wood block prints.

Yes.

That must be a very labor intensive process.

Yes, it can take a lot of time.

And then I make a mylar map [a template] of the finished mock-up.

And it shows me where all the little pieces of the cut-up woodblock prints go and I’ll use carbon paper to transfer that image to the painting surface [supported wood veneer]. And then I move all the cut up pieces from the mock-up to the final surface and adhere them with a bookbinder’s adhesive.

My god, that is an awfully long process!

Ha, yes, it is.

And how long have you been doing this process?

Ah…. I guess I started in…. ’86. I started combining them, the prints into the work, maybe in ’96. So here is an earlier example. This was made from a face my daughter made and I combined it with the print of bamboo root.

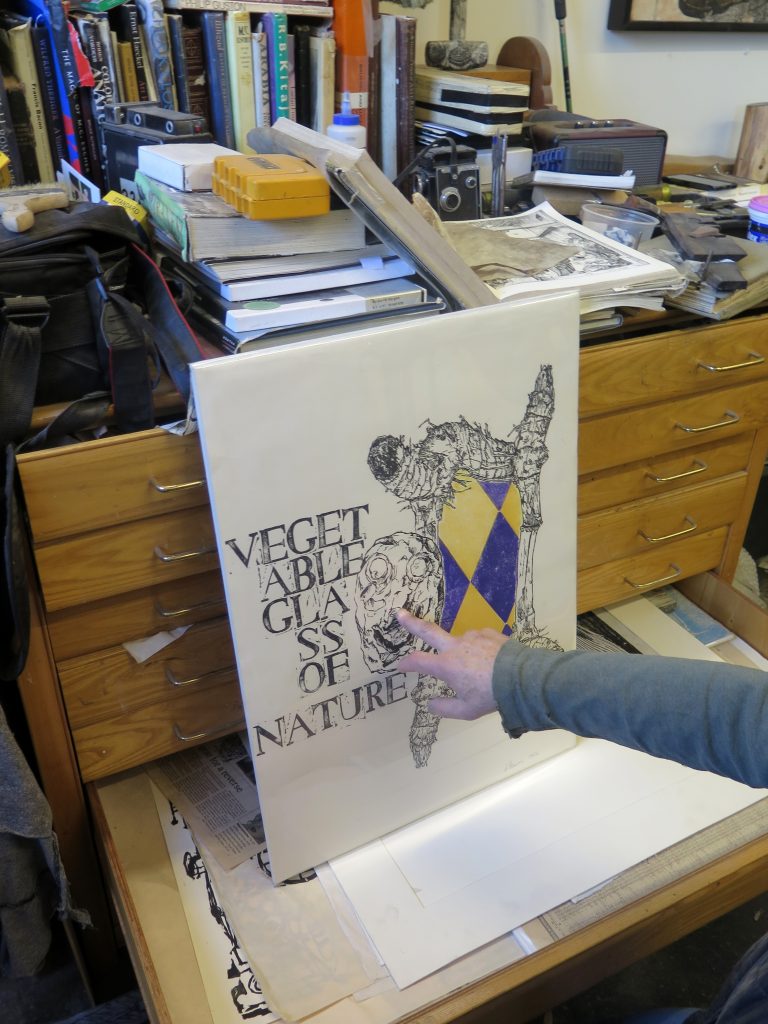

Vegetable glass of nature?

Blake.

So they just got more and more complicated and eventually ended up as these configurations.

[I’m thinking like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.]

So I just always liked woodblock prints and one day I decided to start cutting a piece of wood and thought, “Oh, I can do this,” and it became more and more of the process.

Did you study wood block printing?

Well, no. I was at the Art Institute [San Francisco] studying sculpture for a couple of years but I really hated it and one day in class a paper cup rolled across the floor and that was it, I walked out and never returned. So I never finished. And I went to the Art Academy when it was like one building on Sutter Street. Joan Brown was there and others. But it turned kind of commercial and I quit.

So let’s finish the process.

So, yeah, I start with the figure first and usually begin with the eyes. It’s the hardest part because it is what people are drawn to.

And it informs what the painting is about.

Well yeah. Usually in my figures I use my eyes because I do a lot of self-portraits.

And then after you have applied all the cut up pieces of the block prints to the surface, do you then go back and paint onto it?

No. I hardly ever do that; maybe just to correct some small thing but nothing more than touch-up.

Oh, so the color is all in the print?

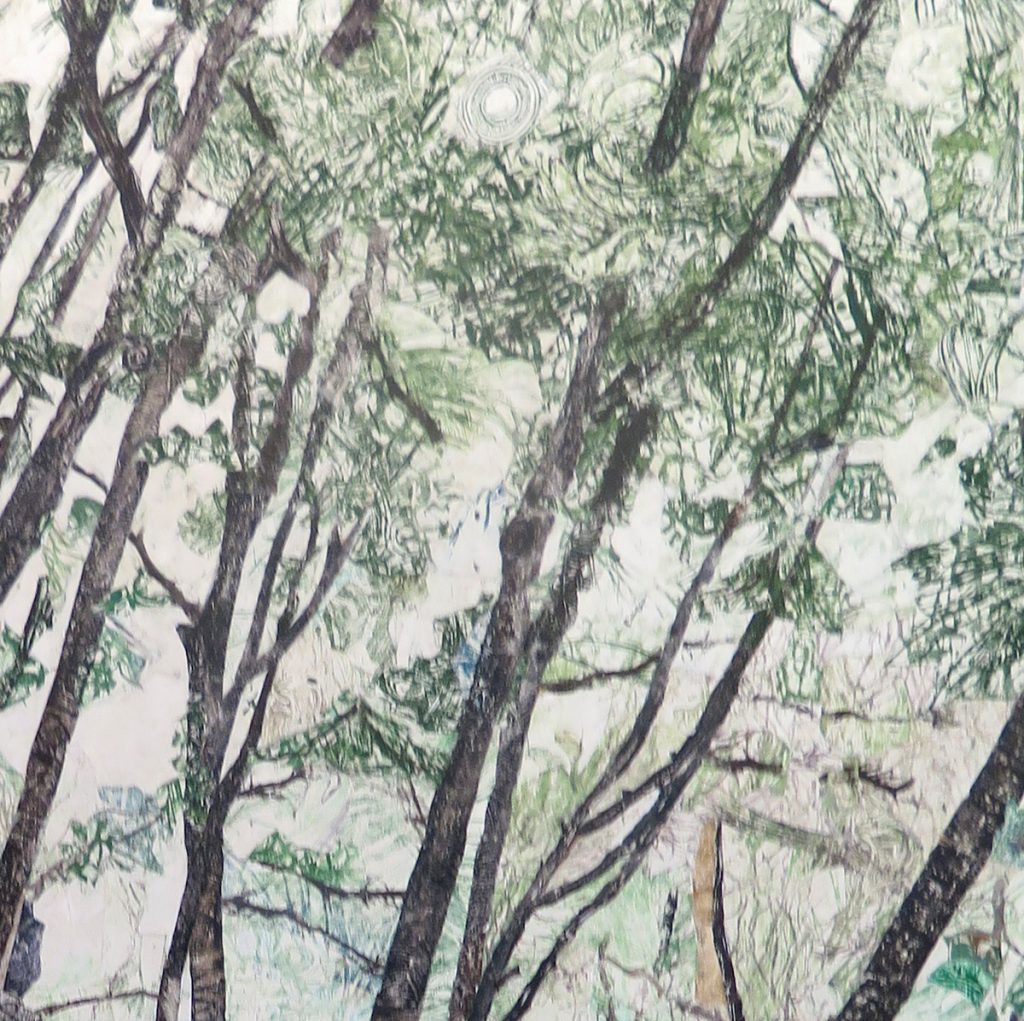

Yes, like the green in this one is the color used to make the prints. [detail]

Unfortunately, this was the point at which the recording stopped. However, we did record Harry’s process in some detail. The following narrative is my recollection of the rest of our conversation.

I was curious how Harry, who is mostly a self-taught artist, had arrived at his method and the meaning of his art. He explained that he had been self-employed and created a workshop and a business of manufacturing architectural moldings and other finely crafted items, including creating various fine finishes. Eventually, he sold the business to an employee but Harry maintains an area of the large workshop as his art studio. This history made me more fully understand where Harry’s attention to craftsmanship, materials and techniques originated from.

Returning to the detail and time-consuming process, Harry explained that he liked working on the woodblock prints, that he found it meditative and calming. The paintings were a two-step process of the exacting work of the printing process that then culminated in the larger image of the finished piece. I thought to myself that it was akin to looking through a telescope first from one end and then from the other, first to see all the minute detail and then to see the whole image. Imagine an astronaut’s first image of the earth from space, a very different view of a familiar reality.

Harry is hung up on time! He likes old things and objects that have a history and tell a story. He isn’t interested in a quick fix. His art is all about the continuity of time, time over long periods, and distances, both familiar and remote.

Harry’s studio is something like a museum of natural history gone awry. One of the woodblock prints is taken from a fly’s long-dead and transparent body, an exoskeleton found at the bottom of a glass beaker after having been there for twenty or more years. [“It was so beautiful but fell to dust.”]

The studio is chock-a-block full of fascinating stuff, from old cameras, books,

found objects of all sorts,

wood-working tools and even large flat files of hidden treasure.

There were several old cameras lying about and when asked, Harry explained that he used them mostly to take pin-hole images.

The subjects of his paintings nearly all derive from photographs although his process has little to do with them other than as reference and a point of departure. However, he has experimented with photographic materials and techniques to create some very magical images. He doesn’t consider these images his finished art but I was struck by the beauty of many of them; one, in particular, not unlike a mythical Chinese landscape.

I wanted to know more about why Harry painted what he painted and again mentioned that I found his work eerie and even a little sinister. He did not think “sinister” was the right word but did go on to say that he was a Jew, that some of his relatives had had numbers tattooed on their forearms, and he opened a large book to show me some photos from the holocaust.

In further discussion, Harry explained that he had always been interested in decay and that explained, in part, his fascination with old things and long periods of time, of history and of storytelling.

I always ask artists why they do what they do. Why do they make their art? And like most artists, Harry’s answer was equivocal. “I wonder what will become of all this stuff. I don’t know. It’s what I do.”