Heidi Brueckner is our 2020 Juried Show winner, and last year, Gearbox alumnus Dennis Hanshew interviewed Brueckner over Zoom for our blog series (linked here). Their conversation is an in-depth look at Brueckner’s art practice and trajectory as an artist. In preparing for my in-person conversation with Brueckner, I wanted to make sure I covered different territory than the 2020 interview, and in particular to bring focus to her new work. Having followed her studio practice over the past year on social media, a few aspects of her work emerged as unique: her exploration of the painting’s “substrate” (what her painting is painted on) and her coruscating and bold use of color.

Her 2020 award-winning piece Tween (Anika) was displayed on un-stretched canvas attached directly to the wall, giving it a tapestry-like quality. Over the past year, she has furthered her exploration of ways to present an unframed and flexible painting and has developed new strategies for creating a durable and interesting surface. In the tradition of artists like El Anatusi (who often re-purposes aluminum and copper wire from bottle caps and foil wrappings to create large wall-hangings), Brueckner has found a use for a material that is plentiful and often a waste product of our COVID-era e-commerce reality…plastic. In particular, she has given new life to the bubble-wrap envelopes that are designed to be a resilient protective sleeve…and it turns out they also work great as a surface for oil painting.

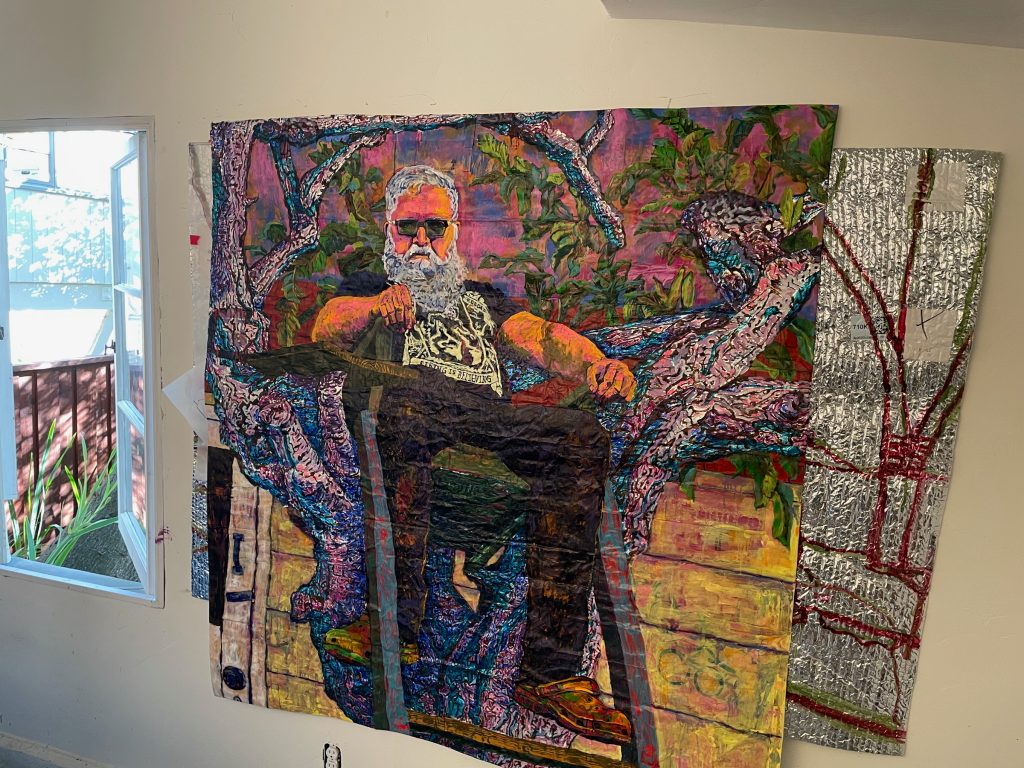

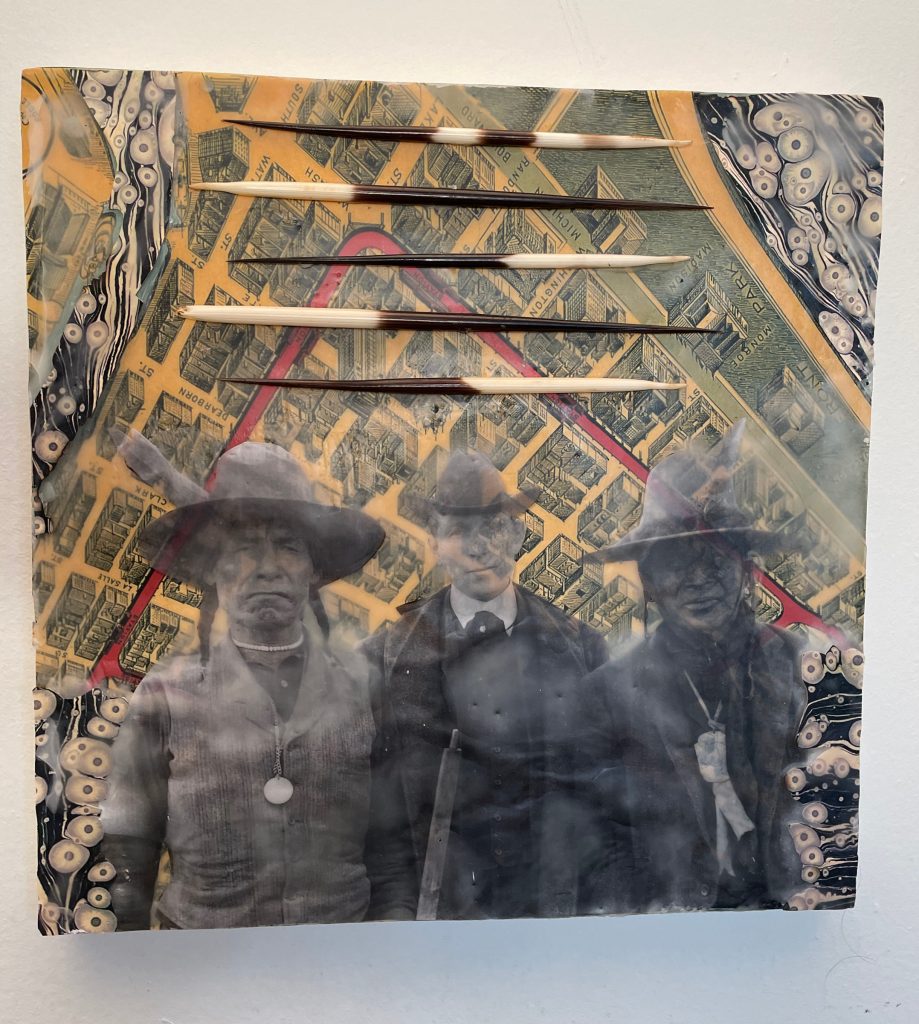

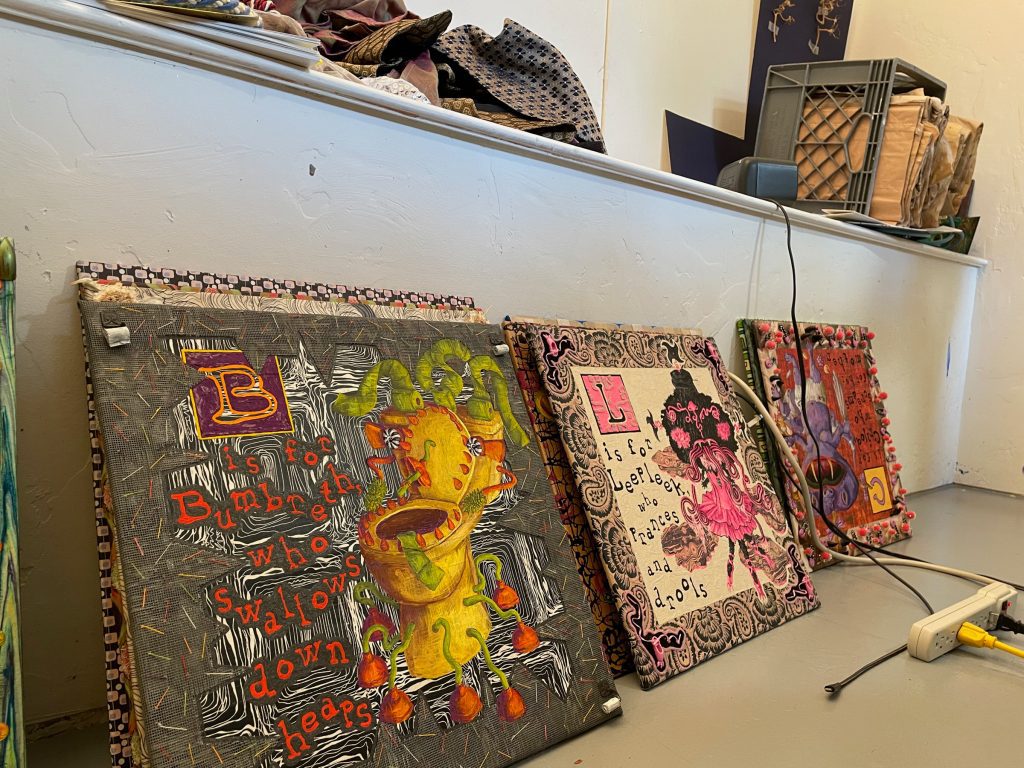

Many of her recent works begin with gluing together the bubble paper to create a barely-discernible rectangle grid. Brueckner then paints directly on the metallic surface, without any gesso. Even in a finished work, there are areas where the metallic sheen peaks through the oil paint, creating a flickering effect in the light. In a striking in-progress piece (pictured below), Brueckner takes the construction of the painting’s surface a step further by sewing handmade papers together on the sewing machine. The paper fibers create overlapping circular designs that is overlaid with the organic embroidered line. This intricate foundation for the painting creates opportunities for the oil-painted brushwork to interact with the textured surface in ways that invite the viewer to step close to her larger-than-life portraits and examine their inner-workings.

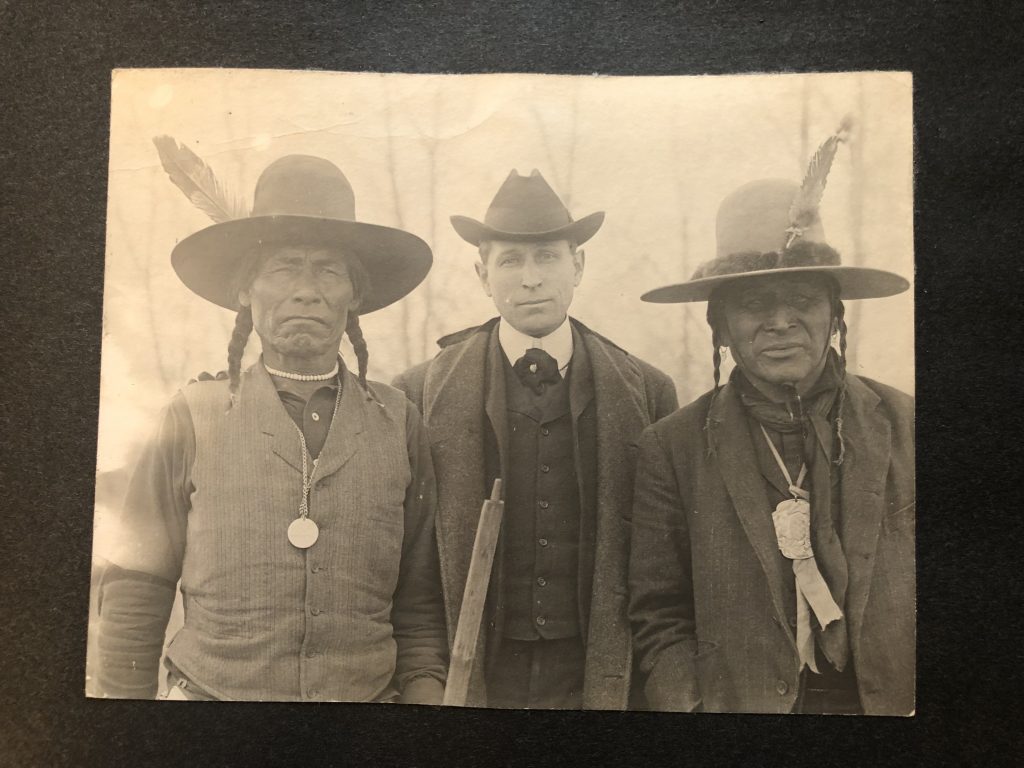

Brueckner’s studio is anchored by a massive work table that houses her palette, brushes, source material for her work and a massive self-healing cutting mat. As we fellowshipped around her table over coffee and pastries our conversation lingered on one item at her table of particular importance–a photo album from her great-grandfather’s work with the Crow Tribe in Wyoming. Brueckner is using this special piece of history to create portraits that ask questions about the indigenous lives her great-grandfather documented in such depth.

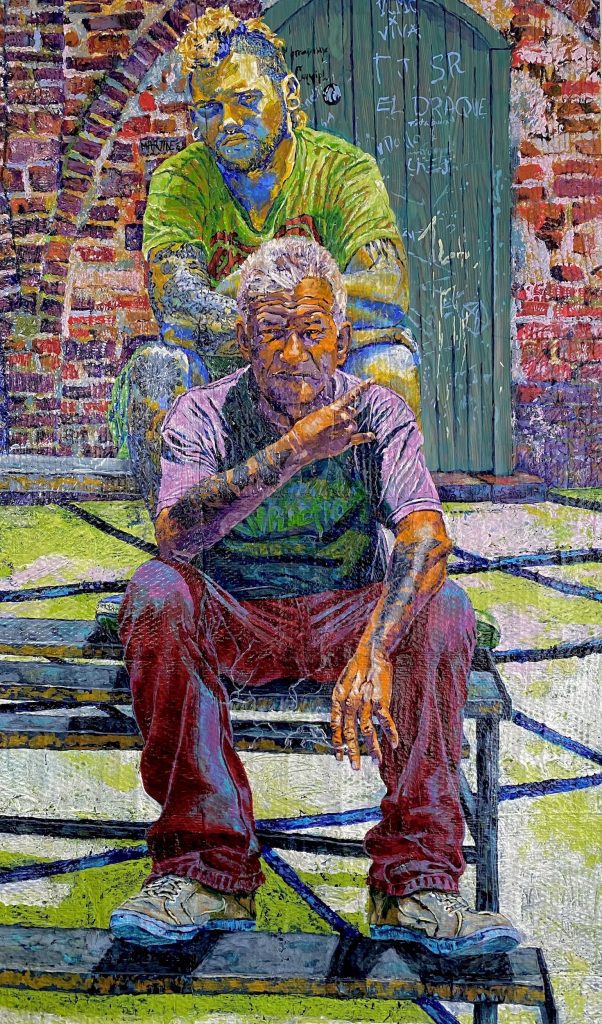

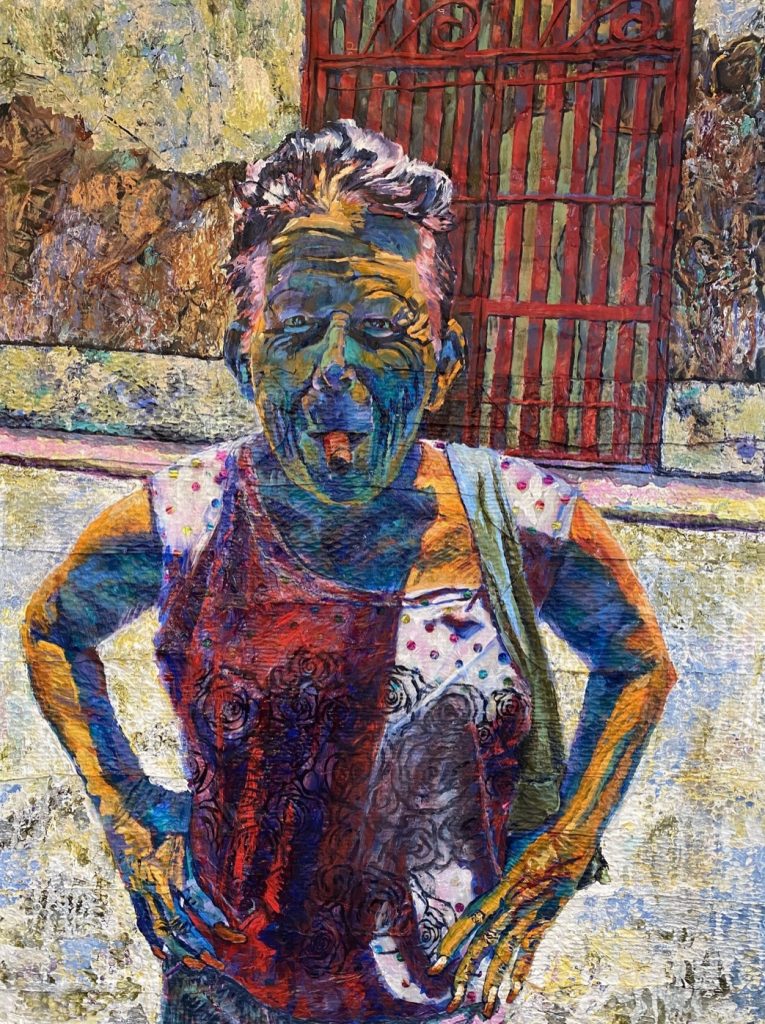

Her space is lit with industrial work lighting and gentle natural light. Brueckner works vertically, with the flexible surface attached directly to the wall. Her portraits have an initial under-painting–done in monochrome line work–that accurately hashes out the proportions of her figures and creates an effective underpinning for the composition. Brueckner’s saturated color palette brings unexpected hues to shadows and to skin-tones. In contrast to the naturally-proportioned figures, the color goes beyond the natural into an expressionistic realm…as if her portrait’s subjects are exuding their auras. Brueckner brings a similar vitality and sense of joy to the the environment around the figure. Trees and foliage are painted with lyrical and calligraphic lines and seem to glow in an otherworldly spectrum.

The people in Brueckner’s portraits connect to the viewer with a piercing and captivating gaze. Drawing from personal travel photographs to Cuba and family archives, the portraits emanate a trust and vulnerability between the subject and the artist. There’s a sense that each of her portrait’s subjects play an important role in their community, and there’s a palpable pride in their presence.

78.25″ x 46.5″ , Oil on Recycled Bubble Paper

Below is an excerpt of my conversation with Heidi Brueckner.

Looking back at your Gearbox interview with Dennis Hanshew last year, it sounded like you were embarking on a focus in portraits. How has that work developed in the past year? What has changed in your studio practice?

I have continued in the same vein since because I think there is a lot more to discover. However, I have started working more with recycled materials. I am also branching out into incorporating other mixed media elements in the paintings very recently, which was something I was working with regularly before this portrait series.

During the deep process of observing someone in order to make a portrait, where does your mind go? How does your relationship change with your subject?

There is a difference for sure between working from live models and from photos—which is what I started doing after the pandemic hit. Live model works are a conglomeration of many moments and a physical and artistic response to a conversation. Working from photos opens up all sorts of compositions and contexts that are difficult to conceive of otherwise. A more one-sided relationship develops in that case, but there is definitely a bonding that takes place anyway. Studying someone’s face so closely is not something one experiences much in in everyday life otherwise. It feels voyeuristic in a way but also enables one to gain love and appreciation for the soul of the person, through observing every nook and cranny of a face which, for me, is the most expressive part of a person. I have painted people I know personally up to now, but have now embarked on painting from photos my great grandpa took of members of the Crow Tribe of Native Americans that were part of his daily life in Wyoming in the late 1800s. The faces of the people are incredible and it has been interesting to paint someone whom I know nothing about. I suppose there is more of an invented narrative that goes through my mind when I look at them for many hours.

48″ x 36″, Oil on Recycled Paper Bags and Bubble Paper

I’ve been following your new work on “recycled bubble paper” with fascination this past year. And in your recent artwork posts, you describe creating a substrate before the painting begins. Can you talk about the “substrate creation” stage of your creative process?

This is some of the recycled material I referred to in the first question. With the pandemic creating an era of intensified mail-ordering, these Amazon poly envelopes started piling up in my house. It was impossible to re-use all of them as envelopes. I started to think about them as an interesting textural surface and decide to see if I could make an unstretched “canvas” from them by cutting them up and gluing them together into a large surface. Because the stuff is indestructible, I am not worried if the paintings will have a long life. I put the material and the paint together through some destructive testing. The combination passed with flying colors. Painting on the surface brings out a really interesting textural element in works that is totally unique. I started painting some people I met in Cuba on the substrate and felt it very appropriate because the materials remind me of the creative way in which Cuban artists work, often incorporating everyday materials in innovative ways into artwork, because materials and resources are often limited.

What are your thoughts about the waste we produce as artists? Why is it important to utilize discarded materials (like plastic packaging) in your work?

It is of course important for all of us to analyze how our actions produce waste and how to modify the way we live and make choices in order to work towards a more sustainable existence. Working with existing materials is part of it for me. It’s also important to realize production of art materials has environmental impact. Trying to work with materials that are more environmentally friendly is a good place to start. For instance, I try to use less acrylic paint than I used to. Making sure to dispose of hazardous materials responsibly and in the proper manner is also key. I make stops at my local hazardous waste facility to dispose of paint residue and solvent laden materials associated with oil painting.

You describe your love for the awkward, stilted, gritty and macabre (which are traits near and dear to my heart as well!) What role does color play in creating a painting that pays homage to the awkward?

I think playing with color is such a powerful tool. I often choose to use expressive, non-local color to heighten the drama in a picture or make it slightly “otherworldly”. The dark, macabre, gritty, have always felt most profound to me. Use of non-local color has translated in an interesting way into the portraiture too. It acts as a kind of “equalizer” in terms of the way people of different races are depicted. Since the color is divorced from naturalism, skin color is, in a way, taken out of the equation. That sets up some interesting questions about how we perceive race and hopefully makes a statement that we should honor all individual people and throw stereotypes out the window.

How did your pair with co-featured artist Joseph Slusky arise? What are you curious about in his work?

This was a curating decision on the part of the gallery. I believe the use of color was what initiated the match. I am happy for the pairing because his work is very strong. I also believe he sometimes titles his work after far-away places. I like to paint people from far-away places as well. I think we both probably share a love of the undiscovered or under-represented.

➡️ Heidi Brueckner’s show with Joseph Slusky Seeing is Believing opens in the Gearbox main gallery on January 6. Click here for exhibition details.