Gearbox Gallery

Contemporary Art

REFLECTIONS

Jane B. Grimm and Rachel Major

November 18 - December 31

Artists' Reception Saturday December 4, 1 to 4 pm

Jane B Grimm

Rachel Major

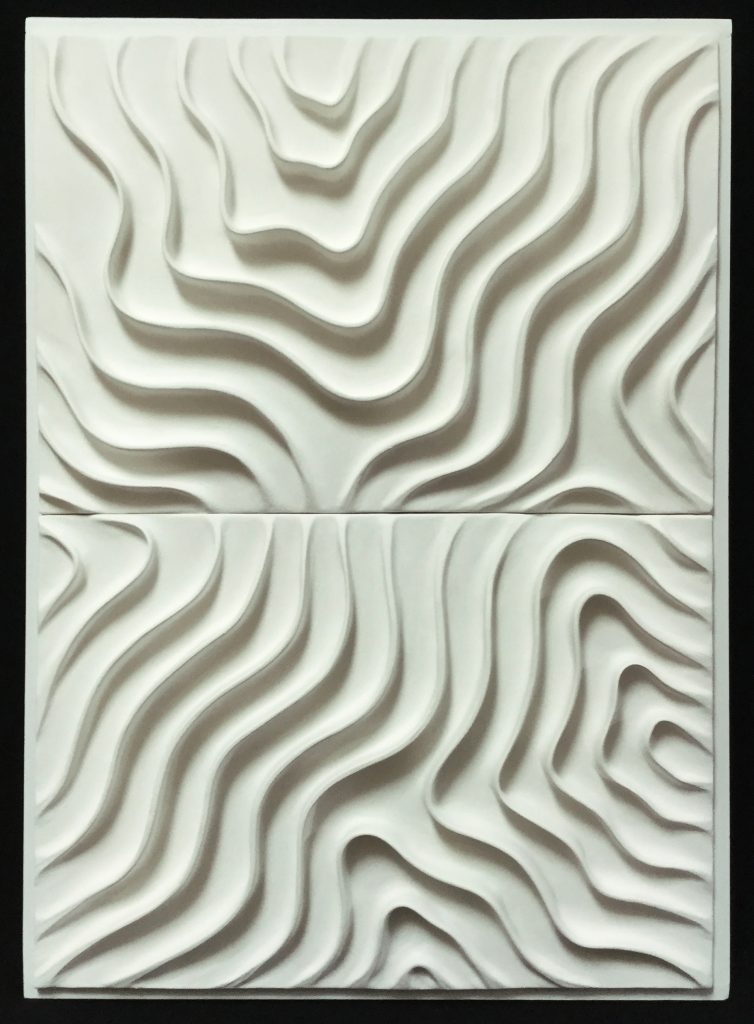

GearBox Gallery is pleased to present Reflections, an exhibition of ceramics by Jane B Grimm and paintings by Rachel Major. Repetition and abstraction bring these two Bay Area artists into formal dialogue. Grimm pushes the material possibilities of clay to build sinuous reliefs and textured forms inspired by plants, invertebrate sea life and music.

Major addresses the power and mythology of meat and its traditional connotations of men as powerful (hunters, carvers, grillers) and women as weak (chick, (fat) cow, (old) crow). Major’s fluid and overlapping silhouettes of hanging game build evocative patterns and challenge traditional representations of power. Major and Grimm mirror and complement each other’s work with their graceful forms and supple compositions made in paint and clay.

About the Artists

Clay, as art mavens of a certain age will remember, was not accorded the status of a respectable art medium until the 1960s and 1970s, approximately concurrent with photography’s acceptance. If the latter had been deemed problematic before then, because of its supposed mechanical nature, and ease reproducibility, clay was considered questionable because of its connection with utilitarian vessels—bowls, jars, and small, unpretentious religious figurines—dating back thousands of years. Bay Area artists served as important trailblazers in clay’s acceptance. Peter Voulkos took advantage of clay’s ability to render sweeping ‘painterly’ gesture with fine detail; Robert Arneson and Viola Frey explored its sculptural potential, both monumentally and parodically; and Stephen DeStaebler embraced clay’s unique aptness for rendering weathered ancient statuary, crumbling and returning to the earth.

Jane B. Grimm, also of the Bay Area, has chosen to explore clay’s possibilities in minimalist or post-minimalist abstraction, with abstract form mediated by the mediums’ material properties and by repetition and process, creating visual metaphors without what Francis Bacon called the tedium of realism or narrative. Think of Eva Hesse’s humanized assemblages of unorthodox and sometimes non-archival materials, for example. Grimm, who works in a similar exploratory spirit with abstraction, but in a time-honored and stable medium, writes:

“My work is meant to stir the intellect[,]… influencing the viewer’s preconception of what ceramic sculptures are… [C]lay is not necessarily synonymous with function or kitsch. … I am exploring the effects of transformation on forms and objects… My work is hand built, primarily using low fire clay and glazes….”

Grimm’s modestly sized sculptures sometimes play on their resemblance to utilitarian objects. The artist began her career, with great success, in the 1970s, making jewelry, before moving to clay sculpture in the 1990s, studying with Frey. Grimm’s sparely poetic work of the past three decades, here represented by freestanding sculptures and wall reliefs mounted on wooden plaques, reflects her mastery of technique and material, along with the imagination and wit that she finds in music—a longtime inspiration evident in her series titles, e.g., Ode, Rondo, Fugue, Rhapsody, Glissando—along with forms found in nature, especially plant and invertebrate sea life. Her work, while pared-down and never representational or realistic, is richly evocative, suggesting, variously, architecture, bird’s nests (Rondo III) topographic maps (Ode XVI), fingerprints (Ode XIII), crystalline formations, wind and weather (Swirl IX, Spiral I), brains and brain corals. The Surrealist Jean Arp, who shares with Grimm an interest in nature depicted abstractly, once wished that his sculptures could be viewed outdoors rather than in the sterile white box of the gallery or museum: that they could be considered natural artifacts. Both Arp and Grimm transmute nature, infusing its distilled spirit into aesthetically and intellectually pleasing objects—maybe even jewel-like—that satisfy the poetic explorer fortunate enough to happen on them.

By: DeWitt Cheng

The subject of still life in art history has a long and rich history, having evolved from small tableaux in Renaissance religious paintings to become, in the Dutch Golden Age, subjects in their own right,, though still charged with symbolic meaning. Glorious bouquets of flowers, exquisitely painted, were offset by skulls, dead game animals. and guttering candles in moralizing memento mori and vanitas paintings, which silently exhorted the viewer to remember mortality and Christian humility. In the nineteenth century, hunting paintings emerged, celebrating the catch of the day in luxuriant detail; William Harnett’s After the Hunt (1885), in the de Young Museum collection, is a masterpiece of trompe-l’oeil, i.e., fool-the-eye, realism.

Rachel Major revisits this theme with a contemporary secular interpretation. The dead animals become “embodiments of [human] power and control” that reveal “tensions between representations of power and weakness”—the human and the animal—between culture and nature.

“I am specifically interested in the power and mythology of meat and how it represents men as powerful (for example: as hunters, carvers, grillers) and women as weak (for example: as it is expressed in our language- chick, (fat) cow, (old) crow etc..). Much of my work juxtaposes images of meat and dead animals with materials and processes that are traditionally female (fabric, needlepoint, organic shapes)…. Cakes, sweets and jello/cake moulds sometimes make their way in my work as well. To me, cakes are similar to meat as well as meats opposite. When meat is associated with strength it is considered masculine and cake is it’s opposite- feminine.”

Major’s Birds, Bunnies and Deer paintings depicts hunted animals strung up by their feet as in Harnett’s work, but abstractly, with overlapping shadows or silhouettes in gray tones against black or white backgrounds, or in bright colors that change hue where the shapes overlap, as if transparent. The images, sometimes symmetrical, suggest photograms and Rorschach tests. Her Stuffed Meats and Sweets and Stuffed Organs sculptures surrealistically marry the wit of Claes Oldenburg’s sewn, stuffed sculptures with the animal-rights activism of Sue Coe. Cuts of meat, their bloody origins counteracted by the plush fabric, stand as metonyms—parts of the whole, in literary terminology—of the factory-farm disassembled animals. A series of quilts and needlepoints take the traditional female art form of the comforter to new, discomfiting places.

By: DeWitt Cheng